Originally published on the British Library Sound and Vision Blog

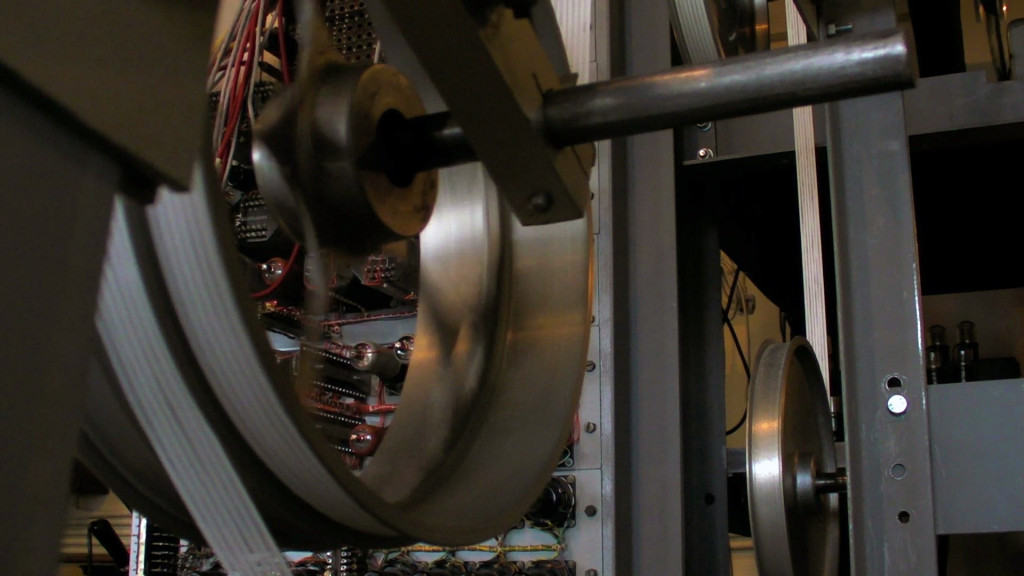

Between January and March 2015, Matt Parker was artist in residence at The National Museum of Computing, Bletchley Park. The residency, which was supported by the Arts Council England’s Grants for the Arts Scheme, was an audio archiving project that resulted in the production of 116 unique audio recordings of some of the world’s most historically significant computer technologies. Within the collection are sounds of the world’s oldest original functioning digital computer, the Harwell Dekatron (also known as WITCH), a faithful replica model of the world’s first digital computer, Colossus and a replica model of the electromechanical decryption device the ‘Bombe’, designed by Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman. In the first of two posts, Matt wrote about developing The Imitation Archive and his experiences during the residency period. His final post looks at producing a catalogue to accompany the archive and using the raw recordings of historic machines to create musical compositions.

Producing the Archive

Having recorded for many days, fighting against the elements of heavy rain, snow and school trip groups, I set upon the task of cataloguing the material. During the recording period, I was careful to speak into each microphone before recording a particular device, announcing what I was recording. I kept the file names constantly updated with time and date so I would be able to follow what happened, when and where, and I tried to record everything as a 96 kHz 24 bit .wav. I took photos with my smartphone for reference of each item and tried to take higher quality pictures with a camera where possible. A thorough reference of microphone placement and signal path was important to the accuracy of the recordings.

I went through each recording, cropping out the noise of setting up and spending as much attention as possible on listening to the main activity or process that the recording was set up for. I tried to record as cleanly as possible, but in some cases it was necessary to clean up the recordings with a bit of EQ and multiband compression; nothing that would alter the core character of the recording at this stage, just faithful archival replication.

In some cases, I recorded with a few options, for example a stereo, mono, and transducer setup all in one multitrack recording. I was wary in the recording process to be careful with phase alignment so I was effectively able to fade between different microphones. I think there is an interesting question to be asked with the notion of subjectivity with the recording process here. How important is it to capture the object as one hears it? How clinical should a recording be? Is there any point in capturing recordings of things that can’t really be heard naturally by the human ear? Do we want to shut out the architecture or environment that an object exists within?

In the case of The Imitation Archive, I felt that it was important to capture ambient recordings of the objects within the space they occupy in order to demonstrate their presence within a particular environment. It seemed like a pertinent decision, and one worth making, given that I was to record Colossus which is set up in a room where the machine was actually used during the Second World War. In the studio, it felt like perhaps I could play with these sounds to find the most interesting combinations sonically.

Composing the Archive

As a composer, I wanted to find an interesting way to work with this new ‘sample library’ of material. More than just working with the archive in this way, I wanted to draw on the themes and experiences of the recording process; the museum, the objects, the themes around the very concept of producing The Imitation Archive.

One of the key things that struck me was the constant durational aspect of these machines. Many of them were designed to run 24/7 without fault or interruption, performing repetitive cycles. I felt that this would be an interesting idea to explore so I chose to focus on the machines in operation as much as possible; the work cycle, the operational cycle. I also decided to make the composition seamlessly flow between sections, a never ending cycle of computing.

I was also very much drawn into the historical narratives of machines at Bletchley and found myself wanting to reflect the architectural relationship with the sounds as much as possible by playing with impulse responses of the rooms (made using a balloon pop so not an exact science!) and convolving the sounds of the recordings with the space impulse response itself. I used impulse response as a filtering method, locating fundamental frequencies that peaked within the recordings. I would push and emphasise these frequencies to turn the machines into instruments playing their own unique keys. I thought it was an interesting discovery to find how some of the fundamental frequencies tended to harmonise with themselves. Some of the machines such as WITCH, Bombe and Colossus have very distinctive mechanical rhythms, and it seemed to make sense to play with this as much as possible. Their repetitive rhythms would occasionally break from the cycle and create a surprise extra half beat or other micro-beat. Overall, I hope I have given a sense of what it might be like to work with these machines day in day out, in different environments, as well as draw on their relationships with the space in the museum as it is today. Similarities and differences all punctuated through a musical composition.

Conclusions and Future Plans

My experience of producing The Imitation Archive has given me a sense that there is much more to explore in the world of computer and technological sounds. I have been working on a further project that is specifically looking at the relationship between modern IT infrastructure, the latest, cutting edge technologies in computing and their architectural habitats.

As I begin to explore the sites of our contemporary internet landscape from a technological infrastructure perspective, new questions are beginning to emerge; how do we reflect the shift from desktop PCs being the locations of our digital content to placing everything in a mobile networked ‘cloud’ system? What are the environmental relationships between these new palaces of a digital world and their local habitat? As computers become increasingly prevalent in our day to day activities, smart devices, the internet of things, connectivity to remote machines, have all changed our relationship with digital technology. Can sound illuminate for us anything about this somewhat abstract and increasingly estranged relationship? My work in this area can be seen on my project website www.thepeoplescloud.org. As I continue to develop this research, I will be starting to produce a PhD at The London College of Communication in September within the Creative Research into Sonic Arts Practice department (CRiSAP).

Working on The Imitation Archive has been a fascinating opportunity for me to consider the historical impact of computing on culture and society. In the future I hope to find out more about the impact of computing on culture and society within the contemporary moment.

The Imitation Archive was supported by Arts Council England’s Grants for the Arts scheme and is available at the British Library (collection C1679)